President Compaoré’s government endured two major internal crises in 25 years, the Norbert Zongo Case and the 2011 crisis. But the violent death of Compaoré’s predecessor, the military ruler Thomas Sankara, became a source of political controversy that has marked Compaoré until today (359).

President Compaoré’s government endured two major internal crises in 25 years, the Norbert Zongo Case and the 2011 crisis. But the violent death of Compaoré’s predecessor, the military ruler Thomas Sankara, became a source of political controversy that has marked Compaoré until today (359).

Marxist organizations that supported the National Council of the Revolution (CNR) presided by Captain Sankara were characterized by infighting. Soon, the disputes reached the army, dividing it in two fiercely opposed sides. The outcome of all this was tragic: Sankara was killed in a shootout on October 15, 1987. With the establishment of the Popular Front that day, Captain Blaise Compaoré, N°2 of the Sankara regime, assumed power and proclaimed measures to ease tensions.

The Thomas Sankara Case

On April 5, 2006, by virtue of its decision n°1159/2003, the Human Rights Committee of the United Nations rejected and classified six out of the eight arguments of the accusing party – represented by Sankara’s widow. Mrs. Sankara accused the State of Burkina Faso of failing to conduct an inquiry into the death of Thomas Sankara, and of persecuting those responsible – allegations actually unchallenged by the State party (360). Based on the International Convention of Political and Civic Rights ratified by Burkina Faso in 1999, only two arguments out of the eight arguments of the accusing party were maintained by the U.N. Committee, based on articles 7 and 14 relative to torture and inequity of justice (361).

The U.N. Committee’s decision ordered an official confirmation by the State of Burkina Faso as to Thomas Sankara’s place of burial, and a compensation for the despair Mrs. Sankara had to endure. The U.N. Committee ordered the State of Burkina Faso to provide the Committee, within 90 days, with detailed information on the measures undertaken by the State of Burkina Faso regarding Sankara’s burial place and the payment of indemnities for anxiety and distress to his widow (362).

The State of Burkina Faso complied with the U.N. Committee’s decision (363).

On December 4, 2014, during the transition period, the Burkinabè military court issued an international arrest warrant for Blaise Compaoré, who – since his overthrow on October 31, 2014 – has been living in exile in Côte d’Ivoire. He was indicted for his alleged involvement in the killing of Thomas Sankara, as part of the open inquiry initiated in March 2015 by the Burkina Faso transition authorities. The international arrest warrant was cancelled by the Supreme Court for lack of form on April 28, 2016 (364).

The Norbert Zongo Case

On December 13, 1998, violent antigovernment protests broke out throughout the country following the assassination of journalist Norbert Zongo. Zongo headed his own weekly: L’Indépendant. Although L’indépendant suffered from rather modest readership figures, it was known by the Ouagalese public for its scandal-provoking investigation cases (365).

Norbert Zongo had published an article earlier that year accusing members of the Presidential Security Regiment (RSP) of torturing to death David Ouédraogo, the driver of Compaoré’s brother, who died on January 18, 1998 (366).

The violent death of the journalist Norbert Zongo and 3 other persons, inside a vehicle on the road from Ouagadougou to Sapouy, on December 13, 1998, started a political crisis until then never experienced by the Compaoré administration (367).

Since the 1980s, the Burkinabè had grown weary of the violent and mortal incidents caused by soldiers during the military regimes and civilians of the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs). Frustration about the impunity that reigned wherever the “forces” were involved was high (368). Massive protests were staged, requesting a halt to violence and impunity (369).

At that time, President Compaoré was attending a Summit on the refugees’ issue in Sudan, unaware of what was happening. He took immediate action upon his return to Ouagadougou to meet these concerns. He installed an Independent Inquiry Commission (CEI) composed of personalities respected for their outstanding morality (370). Reporters Without Borders (RSF) also was a member of the independent inquiry commission, represented by RSF’s president Robert Ménard (371).

Zongo’s murder provided an opportunity for opposition parties, human rights organizations, civic groups, and media representatives to draw attention to the government’s lack of commitment in cracking down on the violence committed by its armed forces. Demonstrations continued into the first part of 1999.

The commission’s inquiry’s report concluded as follows: “The independent commission of inquiry has no formal evidence allowing it to name the perpetrators of the crime. However, it has identified contradictions and inconsistencies in the evidence presented by a number of suspects of the Presidential Security Regiment (RSP), regarding their whereabouts on December 13, 1998. That means we have not been able to identify the culprits but only serious suspects (372). ”

The six suspects belonged to the RSP. At that time, the RSP was composed by more than 1,200 men, among whom 150 were in charge of protecting the Head of State. The remaining 1,000 RSP military were notably involved in the fight against terrorism.

The investigation report is accessible to the public online (373).

During 1999, the antigovernment unrest intensified. The ruling party CDP dismissed the commission’s findings as reflecting “partisans concerns (374).” But President Blaise Compaoré, in reaction to the commission’s conclusions, during his broadcast to the nation, announced “the reorganisation and the reallocation of barrack quarters in the presidential guard regiment and that he was bent on facilitating the course of justice which according to him, has the task of resolving the issue once and for all (375)”.

In parallel to the legal proceedings and to appease violent demonstrations by the Collective of the Democratic Mass Organizations and Political Parties, Compaoré created a 16-member College of the Wise on May 21, 1999, headed by Mgr. Anselme Sanou, the Bishop of Bobo-Dioulasso and including 3 former heads of state – Lamizana, Zerbo and Ouédraogo, all retired military – to help create an environment for reconciliation and peace (376).

Following the recommendations of the College of the Wise, a unity government was established (377). In November 1999, Compaoré created two new bodies: the Consultative Commission on Political Reforms, and the National Reconciliation Commission, whose mission was to make concrete proposals for resolving the continuing crisis.

Zongo’s death also led to important electoral reforms. An independent electoral commission was created, and the electoral code was revised (379). A single ballot system was introduced to improve accuracy and transparency for the next 2002 legislative elections (380); another measure was that political parties with a running candidate in 2005 could benefit from public financing. Furthermore, the opposition leader would henceforth be appointed third vice president in the national assembly.

Outcome of the Norbert Zongo Case : Marcel Kafando and Sergeant Edmond Koama were sentenced to twenty years’ imprisonment, and soldier Ousséni Yaro to ten years. Marcel Kafando was charged with Zongo’s “murder” and “arson” in February 2001. However, in July 2006, the case was dismissed for lack of evidence, after a key witness retracted statements that formed the basis for the charges. The Zongo Case made civil society more powerful and elections more transparent and better organized (381). It also showed the weakness of Burkina Faso’s judicial system.

Furthermore, Burkina Faso became the first country in Africa where the President and all the living former presidents, ask forgiveness to all the victims of political violence since independence

The National Day of Forgiveness

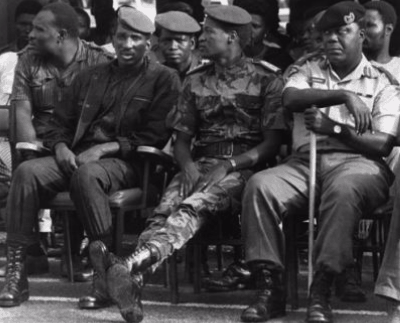

With his predecessors and victims of wrongful dismissal and political violence, during the National Day of Forgiveness, March 30, 2001

Following the recommendations of the College of te Wise, Compaoré proclaimed a National Day of Forgiveness to right the wrongs perpetrated by all regimes that had come to power in Burkina, and to apologize to the victims of wrongful dismissal and political violence – and their relatives – since the country’s independence in 1960 (382).

On that Day of Forgiveness, held on March 30, 2001 and in the presence of the three former Presidents still alive, in his own name and in that of all of his predecessors, Blaise Compaoré asked all the victims and their families for forgiveness for the political violence and unjustified dismissals perpetrated since the country’s independence, with these words :

“People of Burkina Faso, on this solemn occasion, in my capacity as president of Burkina Faso ensuring the continuity of the state, we ask for forgiveness and express our profound regret for the torture, crimes, injustices, bullying, and all other wrongs committed by the Burkinabè on other Burkinabè in the name of and under the protection of the State, from 1960 to this day” (383)”

Blaise Compaoré

A compensation fund was created in favour of the families of the 106 victims of political violence identified since 1960, including Thomas Sankara. Each family was granted 20 million FCFA ($ 30,490) in compensation for the victim, 2 million FCFA ($ 3,049) for each widow and 1 million FCFA ($ 1,524) for each child ; on average 30 million FCFA ($ 45,735) was allocated per victim. To this end, 4,144,091,108 FCFA ($ 6,317,626) were released to compensate the victims and their entitled relatives. On April 30, 2009, 3,919,477,437 FCFA ($ 5,975,204) had been granted to victims (384). The Compaoré regime rarely forbade any protests and never had any political prisoners (385).

Accusation of supporting “Les Forces Nouvelles” in Côte d’Ivoire

Often accused of sponsoring rebellions all over West Africa, one of the most persistent allegations had been Compaoré’s support of the rebellion in neighboring Côte d’Ivoire. The rebellion of the Forces nouvelles (FN) started when Laurent Gbagbo, upon his ascension to supreme power, vigorously embraced violent ethnic propaganda against the Ivorians from the North, as well as anti-Burkinabè politics (386). Consequently, the ethnic conflict – existing since the late 1990s – further deepened.

On September 19, 2002, rebel groups simultaneously attacked three cities, including Abidjan – although they left the commercial capital the same day. On September 20, Côte d’Ivoire was split between a mainly Muslim North, seized by rebels, and a mostly Christian Loyalist South (387). In his book entitled Wars, Guns and Votes, Paul Collier even suggests that while Gbagbo was still an opposition leader, his armed militia the Young Patriots was also financed by Compaoré – for the latter was annoyed by the xenophobic policies swiftly embraced by Gbagbo’s predecessor President Robert Gueï in a political turnaround (388).

Xenophobia and ethnic tension appeared for the first time in the 1990s when the Ivorian economy, very dependent on commodity prices, started to suffer. Before that, one of President Houphouët-Boigny’s main growth strategies, in the time span between independence and 1980, was immigration (389). By the 1980s, 40% of the labor force were immigrants – and mostly Burkinabè (390).

The meltdown in Côte d’Ivoire started when its over-powerful president Houphouët-Boigny passed away (391). Anti-Burkinabè rhetoric gained ground from then on, reaching a dangerous peak when Gbagbo became president (392). Crimes such as the murder, massacre, kidnapping, rape, torture, and humiliation of Burkinabè living and working in Côte d’Ivoire for generations ensued (393).

With more than 3 million Burkinabè living in Côte d’Ivoire (some Africa analysts even estimate their numbers to represent 30% of Côte d’Ivoire’s 20.3 million inhabitants (394)), Compaoré had every interest in being the ultimate guarantor of their security. In 2003, Burkina Faso’s Prime Minister reported that between 2002 and 2011, more than 1 million Burkinabè living in Côte d’Ivoire fled to their ancestor’s homeland, thereby increasing the risk of destabilization of one of Africa’s most stable countries (395).

France’s intervention with its military force “Licorne” in Côte d’Ivoire to protect its 1,000 citizens, was never contested by the international community (396), while Burkina Faso – whose community totals more than 3 million people – had to stand by and watch.

Bound by strong historical and cultural ties, with more than 3 million Burkinabè living and working in Côte d’Ivoire among whom more than 1 million were already repatriated in Burkina as refugees, and given the strategic importance of Côte d’Ivoire for his land-locked country, Compaoré had all interest in reviving the peace process.

On March 4 th, 2007, Gbago and rebel leader Guillaume Soro signed a new peace accord in Ouagadougou, brokered by Blaise Compaoré (397). The 2007 Ouagadougou agreement led to Guillaume Soro being named prime minister; deadlines were fixed for a disarmament process and for the nationwide issuing of new identity papers (398). Compaoré’s country men highly appreciated his initiatives to solve the Ivorian crisis. And, 2008 was a year when his popularity hit its peak.