The 1983 Putsch: Compaoré Installs Sankara

Very quickly, President Ouédraogo and his Prime Minister Sankara clashed. Tensions between both men reached a peak, and Sankara barely concealed his intentions of taking Ouédraogo’s place (101).

IMPORTANT DATES

- 1983, April : Compaoré meets Muammar Gaddafi

- May 17 : Prime Minister Sankara jailed

- May 19 : Compaoré resists creating the “Republic of Pô”

- May 30 : Sankara and Lingani are liberated

- June 15 : Compaoré leaves Pô to attend a reconciliation meeting with President Ouédraogo in Ouaga

- July 1 : Compaoré calls for revolutionary patriotism

- Aug 4, 1983 : The country’s 5th military putsch – Compaoré installs Sankara as President

In April 1983, Compaoré met Muammar Gaddafi with his revolutionary green book in Tripoli. It was Gaddafi who introduced him to another revolutionary: Jerry Rawlings, presiding over Ghana. Compaoré presented Sankara to the latter as the future head of state, if ever they succeeded in coming to power.

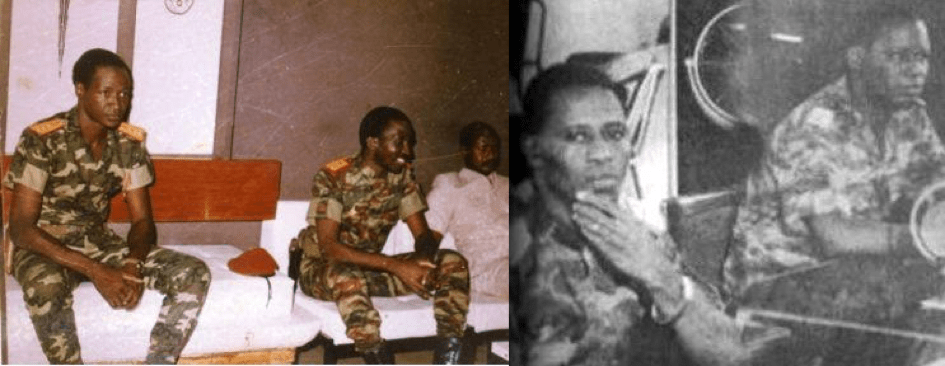

Clashes between President Ouédraogo and his Prime Minister Sankara intensified. In the night of May 17, 1983, tanks surrounded Sankara’s home in Ouagadougou, and Sankara was put in jail (102). At that moment, Compaoré was in Bobo Dioulasso. When President Ouédraogo’s men came to arrest also him, he was already on the road to the commando military training center (CNEC) in Pô, where he had 500 men under his command (103).

Compaoré sent a letter to Ouédraogo with the message that, “Given the fact that CSP’s Charter does not allow the President to imprison his Prime Minister, we are at odds.” Breaking away from Upper Volta, Compaoré decided to put up a sign at the entrance of the city which read: “Republic of Pô.” Many students of Ouagadougou’s University joined Pô. It became the place to be for those looking for a lively and animated revolutionary atmosphere (104). In supplying Po with arms, Compaoré earned the support of Libya and Ghana (105).

The duel between Ouagadougou and Pô that lasted from May until August 1983 resulted in both the liberation of Captain Thomas Sankara and another comrade Major Jean-Baptiste Lingani on May 30, 1983, and the replacement of the Army Chief of Staff Colonel Yorian Gabriel Somé by Colonel Yaoua Marcel Tamini (106).

On June 15, 1983, Compaoré left Pô for Ouagadougou to attend a reconciliation meeting with President Ouédraogo. But having been informed about an attempt to his life awaiting him in the capital, he went back to Pô, then left again for Ouagadougou but this time accompanied by 50 of his men. While attending the reconciliation talks, he leafletted the crowds. Within a very short time, his revolutionary pamphlet had received a huge number of “likes”- to put it in modern terms.

Back in Pô, he asked for Rawlings’ support. In a letter to Rawlings, he pointed out that if Rawlings would not back him, Ghana would have to face Togo and Côte d’Ivoire, their reactionary neighboring states, all alone. It would mean in the long term a certain death for Ghana’s revolution. Rawlings recommended him to reinforce Pô. Compaoré did so and on July 1, 1983, he was leafletting again, calling for revolutionary patriotism.

On August 4, 1983, armed by Gaddafi – via Ghana – and with 50 trucks taken from a Canadian private company Lavalin operating near Pô, Compaoré entered the presidential residence for the second time – but this time to remove Jean Baptiste Ouédraogo (107).

During the coup, Sankara was again under home arrest. On August 4, 1983, Sankara came to power thanks to the support of Blaise Compaoré and his commandos of Pô – the “Centre national d’entraînement commando” (CNEC) (108).

1983-1987, The rise and fall of an upright revolution

The 1987 coup d’état was bloodier than the previous military coups of 1966, 1974 and 1980. The political violence that followed took root in the 1983 coup. It marked also the beginning of a historic revolution (109).

The population initially applauded it, as they did with Saye Zerbo’s coup in 1980. Many hailed Thomas Sankara as the newly appointed Head of State, because of his unorthodoxy and for being outspoken.

Sankara and Compaoré were idealistic, unpretentious young men who wanted to bring dignity and hope to their country. They changed its name from the geographical banality of Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, meaning “The Land of Upright People (110).”

They put forward an aggressive program to uplift the country’s eight million citizens, championing local production and the consumption of locally-made goods (111). Burkina Faso became famous for its odd and non-conventional revolution, a source of pride for many.

The Revolutionary Council “Conseil National de la Révolution” (CNR) organized the vaccination more than 2.5 million children in a three-week span. It also got over 350 communities to build schools with their own hands (112). Between December 1983 and February 1984, the CNR abruptly ended all the privileges of the traditional chiefs (113). The luxury cars of the previous regime were sold and all ministers made to fly economy class. On September 22, 1983, championing women rights, the CNR proclaimed “men-only market days.” On these days, the men had to do the shopping (114). Prostitution was banned and nightclubs were shut.

Sankara’s ideas were spectacular, although often unrealistic and woolly, like in 1985 when he declared free housing for all Burkinabè and forbade the importation of fruits and vegetables (115). Back then, many food supplies came from Côte d’Ivoire. The military ruler was acclaimed for his sharp, colorful remarks about poverty, development and ”imperialist” interference of international powers in third-world affairs.

By deeply upsetting many of his peers, Sankara’s diplomatic relations rapidly deteriorated (116). His programs did not put an end to the country’s devastating poverty. Whilst Burkina Faso remained heavily dependent on foreign aid, Western countries increasingly drifted away from the scene (117).

1983-1987, Growing militarization and escalating repression

From the start, all former politicians were strictly forbidden to undertake any political activities. They were placed under house arrest and could not receive more than three visitors at a time (118).

Between August and November 1983, the government put emphasis on the creation of Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs) as the Revolutionary Council’s local branches. Ubiquitous in villages, in the administration, in military units and schools, their mission was to denounce anti-revolution people, to assess the work of civil servants, and to supervise the participation of everybody in the fields (119).

The CDRs were accused of using – on a wide scale – brutal methods including violent intimidation, oppressing surveillance and the settling of scores (120). These civilian militias and their repressive actions left a lasting mark on the country’s population and leaders (121).

“Sankarism” also committed deadly abuses, such as the execution of Colonel Yorian Gabriel Somé on August 9, 1983: International Crisis Group (122). Seven men suspected of plotting against the government were executed on Pentecost Monday June 11, 1984. Known as the “Suppliciés de la Pentecôte” (the Whitsun Tortured), they marked the country’s memory with sorrow (123). This approach of “physical elimination” continued beyond the revolution (124).

The Popular Revolutionary Tribunals (TPRs), being the third revolutionary institution after the CNR Council and the CDR committees, had jurisdiction to judge political crimes, attacks against the state, and the abuse of public funds. There were neither public prosecutors nor lawyers for the accused, who had to defend themselves during trials that were often broadcast live on radio (125). This public humiliation caused dishonor and distress to many families and led in several cases to suicide.

TPRs also existed on provincial and local level where the “judges”, were picked out among the villagers themselves. Many of these “conciliation” trials were only about settling old scores, often inspired by jealousy and rivalry between neighbours (126).

The TPRs announced the dismissal of over 2,000 civil servants (127). The latter particularly suffered from abuse by these revolutionary tribunals as well as from a high level of taxation (128). On March 22, 1984, more than 1,300 primary school teachers and members of the “Teacher’s Union” (SNEAHV) were dismissed after going on strike. Sankara suspected them of scheming to destabilize the country (129).

Under permanent curfew, Burkina Faso soon became a country where human rights were crushed down and basic freedoms of association or press no longer existed. All media were banned except for the State-owned. The newspaper “L’Observateur” was forbidden and its office was burned down (131).