October 1987, With or Without You

Sankara’s plan to repress all left-wing organizations escalated into a definitive dispute with Compaoré, the second in command of the “Conseil National de la Révolution” (CNR) (132).

Compaoré started questioning the harsh realities, and wanted to disarm the CDRs. The isolated country was politically and economically on its knees. Mocking the misery and shortages in Brezhnev’s USSR, the German Chancellor, Helmut Schmidt, made the following statement (133):

“ The Soviet Union is Upper Volta with nuclear missiles ”

Helmut Schmidt, German Chancellor

The climate of surveillance and distrust among the CNR council members deepened in the period to follow. Bitter controversies widened the divide between the two men, so much so that even the people in the streets of Ouagadougou started talking about the two sides coming at dangerous odds.

On October 2, 1987, Sankara addressed the 45 CDRs in a speech, asking the committees to reconfirm their support to his policies. But revolutionary morale was at its lowest; only 4 CDRs adhered. On October 4, during its council meeting the CNR members requested Sankara to reorient his policies, thus rectifying the Revolution. It needed to be either completely reworked or dropped as a failure. Sankara refused (134).

The exact circumstances that led to the killing of President Sankara and twelve of his men on October 15, 1987 are still subject to various interpretations (135). Accusations that other countries were behind a planned coup remain controversial (136).

“Burkina Faso’s revolutionary leader was killed on October 15, 1987, perhaps after he had told soldiers loyal to him to eliminate his supposed ally. He sought to give his country dignity”

The Economist (137)

The speech given by Italian parliamentarian Marco Pannella in 1984 during his meeting with President Thomas Sankara gives an idea as to how the CNR came to an end:

“Mister President, please hear me out. We have just met. I don’t know Blaise Compaoré and the other leaders. Should you refuse to draft and adopt a constitution, and to get elected, your own are bound to kill one another.

Simple minds will hail the dead and vilify the living.… But the truth will lie elsewhere. It is inscribed in the course of your joint action. You are but in the midst of acting out a Greek tragedy (138)”

Marco Pannella

The lethal collision between two Marxist-inspired military camps started a never-ending blame game, each side accusing the other one of having planned an assassination plot (139).

This blame game is still going on today and fueling the myth of two young, brilliant and handsome revolutionaries, Blaise and Thomas, and the tragic end of their friendship.

No matter which version one prefers to believe, the bare facts are that a revolution came to an end that went pretty much out of control on human rights issues, while making true the old saying that “Revolution devours its own”. But much legitimate criticism has been uttered as to the new regime’s lack of information on Sankara’s death (140).

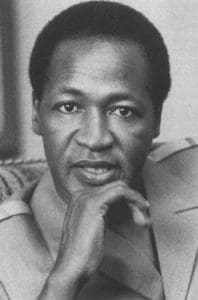

Compaoré admitted that, “In practice, the treatment of Sankara’s death file and the investigation were well below the standard a liberal democracy should adhere to.” Later, when questioned about the October 15, 1987 events, Compaoré put it as follows:

“What happened to us was no different than what happened elsewhere in the world. Closed, totalitarian regimes that are hostile to freedom never end well. The Revolution was a unique experience, but it showed its limits. When this kind of revolution is unable to maintain freedom, it cannot work.

Taking into consideration the context and the time of emergency, it’s understandable that the investigation into Thomas’ assassination has not been conclusive. Burkina is not the only country to have witnessed such unresolved affairs. (141)”

Blaise Compaoré

Rectification of the Revolution: the arrival of a new political era

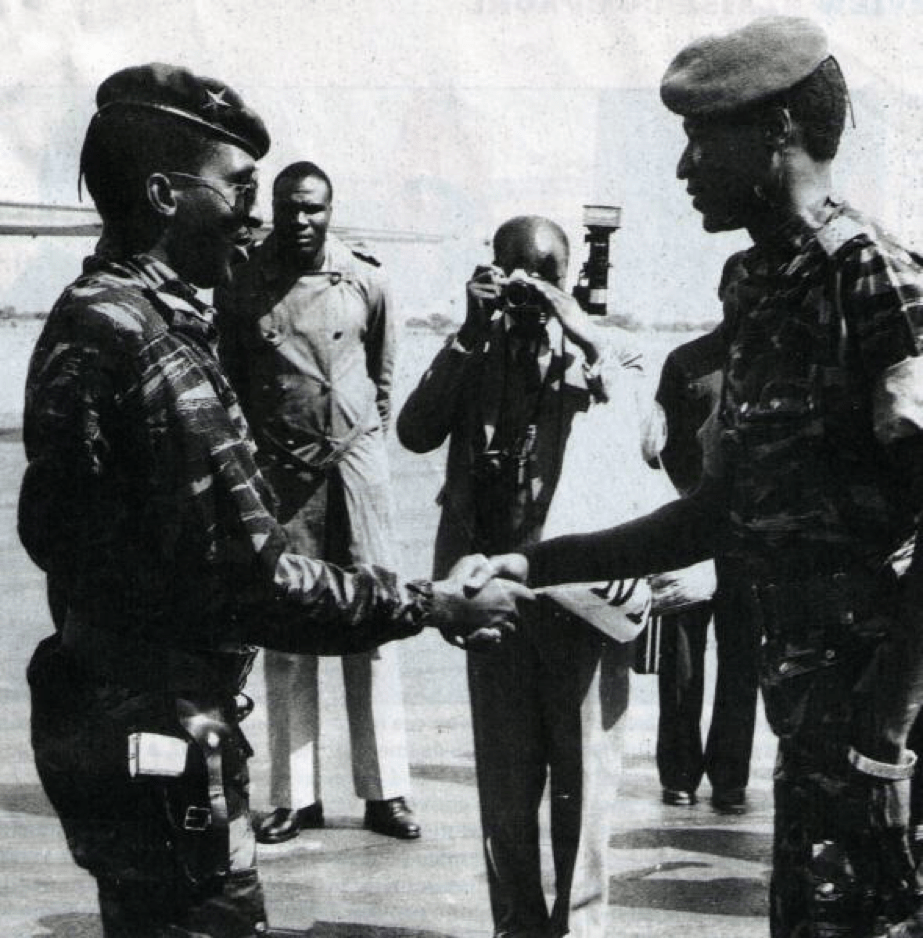

Compaoré took power on October 15, 1987, putting an end to an endless series of coups, curfews and political tensions that had marked the country since it gained its independence in 1960 (142).

Although always the game changer since 1982, Blaise Compaoré never assumed the supreme power himself (143). Only when the revolution that he and Sankara had started, came to an abrupt end, he assumed his responsibilities.

The “Rectification” of the revolution took place without curfew, without any special court of emergency, and without any particular feelings among the populations, too tired by ideology, by the economic slump it had caused, and by the permanent state of emergency they had endured during a constant climate of “coup d’état” that lasted for nearly 30 years (144).

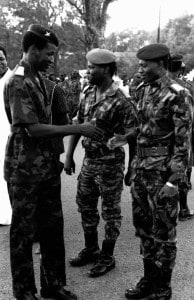

President Compaoré rectified the revolution by compensating the victims of wrongful dismissal and political violence during the revolution, and by reinstating 1,300 teachers the CNR had dismissed on March 22, 1984 for striking as well as more than 2 000 officials victims of wrongful dismissal during the revolution (145). He also immediately ordered to disarm and dismantle the CDRs.

At first, Henri Zongo and Jean-Baptiste Lingani, two other historic figures of the 1983 revolution fiercely opposed the disarming of the CDRs and afterwards the suppression of these civilian militias. They threatened to boycott the process. On September 18, 1989, the Chief of General Staff of the Armed Forces, Commander Jean Baptiste Lingani and Captain Henri Zongo ordered the army to block the plane of the President of Burkina Faso and arrest him on his return from a working visit to Russia, Yemen, China and Japan. The presidential plane was immobilized at the end of the runway, but the army refused to join the putsch. Both men appeared before the military court. They were charged with mutiny and executed on September 19, 1989 (146).

Focused on making the most of his allotted time, President Compaoré is tough and sometimes without mercy. As he will later describe himself (147):

“ I am neither a devil nor a saint ”

1987-1990, Burkina Faso in advance of La Baule

From the very beginning, Compaoré invited everybody without exception to participate in the creation of political parties and in the drafting of a new Constitution, hence creating participatory political governance (148).

The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989 had just marked History. By advocating a multi-party system, Compaoré was in keeping with the times; he was even ahead of French President Mitterrand’s famous La Baule speech on June 20, 1990, spurring African Heads of State to welcome democracy (149).

The new “Front Populaire” (FP) regime installed a transition period. President Compaoré immediately initiated a democratization process that went into labor, and gave birth to multiple political parties throughout 1988 and 1989 (150).

Blaise Compaoré consolidated his power by combining democratization and repression. He obtained major political gain by creating, in April 1989, the Organisation pour la démocratie populaire/Mouvement du travail (ODP/MT), rallying several small left-wing groups in the Front populaire (151).

Thanks to political will, common ground was founded among the different parties from the left to the right, writing a draft Constitution in 1990 with the support of different social forces; traditional chiefs, women’s organizations, religious leaders and other influential figures of civil society.

This great work as well as a consultation that brought 22 political parties to the table permitted the adoption of a Constitution by referendum on June 2, 1991 (152). The Fourth Republic was founded, paving the way for its first elections.

Respect of the Constitution versus national sovereign conference

Blaise Compaoré, Gérard Kango of “Mouvement de Regroupement Voltaïque” (MRV), the leader of the “Union des Verts pour un Développement du Burkina (UVDB)” Ram Ouédraogo, Hermann Yaméogo, the son of the country’s first president with “Union nationale pour la Démocratie et le Développement (UNDD)” and leftist leader Josef Ki-Zerbo were the running candidates for the presidential elections.

Blaise Compaoré, Gérard Kango of “Mouvement de Regroupement Voltaïque” (MRV), the leader of the “Union des Verts pour un Développement du Burkina (UVDB)” Ram Ouédraogo, Hermann Yaméogo, the son of the country’s first president with “Union nationale pour la Démocratie et le Développement (UNDD)” and leftist leader Josef Ki-Zerbo were the running candidates for the presidential elections.

At the very last moment, all candidates except Compaoré abandoned the principle of universal suffrage for choosing the new president, and rallied around the concept of national sovereign conference, an alternative to elections and advocated by former colonial power France (153). The national sovereign conference would appoint “behind closed doors” a prime minister with more executive power than the country’s elected president.

In Compaoré’s view, a national sovereign conference meant returning to the starting line: granting a non-elected person enormous power without having to account to the people under his governance. Blaise Compaoré refused to organize a national sovereign conference, insisting on the need to respect the freshly adopted Constitution. In vain. Compaoré was the only candidate in the December 1991 presidential elections (154).

The Fourth Republic’s first presidential and legislative elections

Blaise Compaoré was elected President of the Republic on December 1st, 1991. With the return of multipartism and the constitutional order in 1991, he won the first democratic elections with 86.19 % of the vote: Freedom House (155).

Only 25 % of the registered voters voted, for the population had grown weary of the controversial and tension-filled climate that seemed to have pursued the country since its independence (156).

As the opposition boycotted the polls, President Compaoré asked the political parties to join him in an inclusive government (157). They accepted his proposal, and the legislative elections were held in May 1992. The ODP/MT party of Compaoré won 78 of the 107 seats in the National Assembly (158).

Given the country’s history of social struggle and Marxist-inspired revolutionary tendencies, the merit of changes Compaoré brought about for enabling multipartism and democracy, is undeniable. Thanks to him, growing up or getting old under curfew was no longer part of the Burkinabè’s daily life reality.